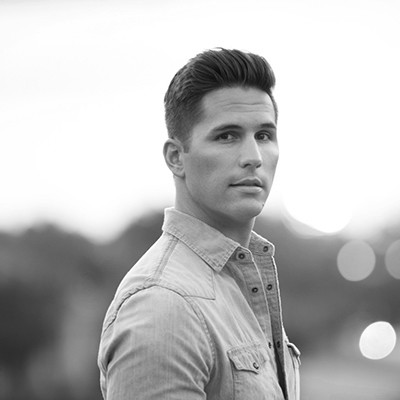

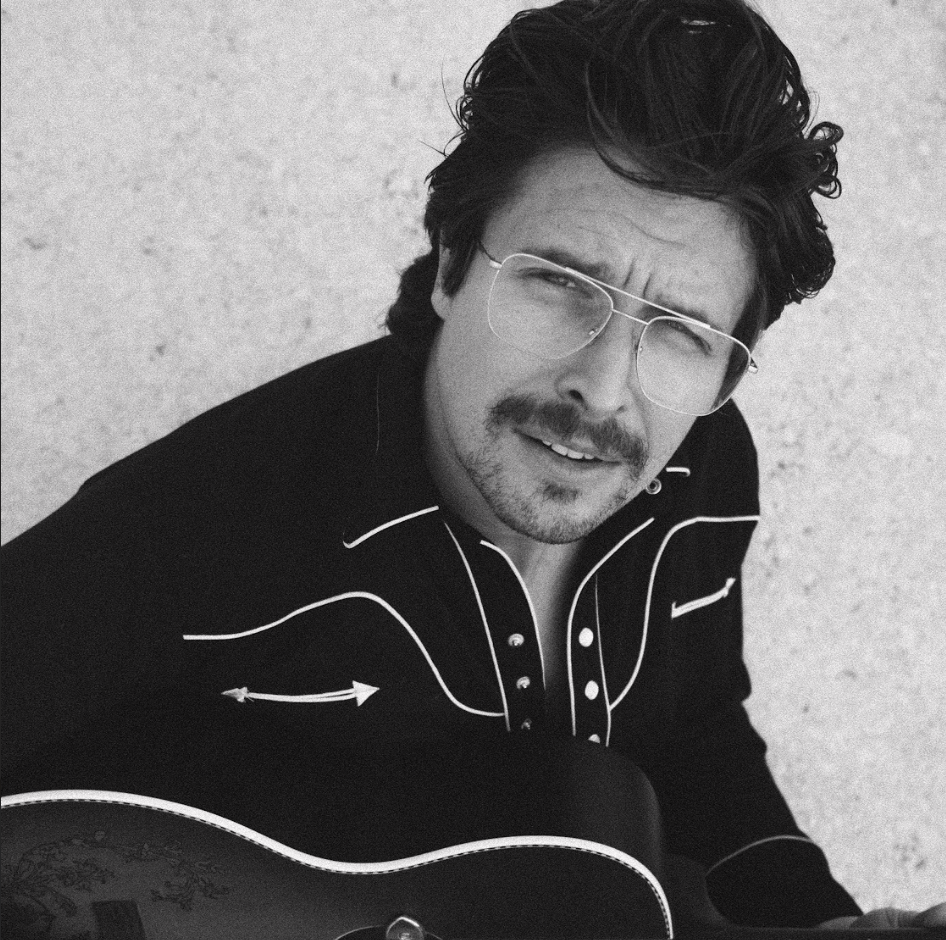

Frank Rogers

Good luck at pinning a style on Frank Rogers. As a producer, songwriter, publisher, and independent label owner, he’s had some level of involvement on some of the most diverse commercial sounds that have emerged out of Nashville since 1999. He’s produced and collaborated with acts such as Brad Paisley, Darius Rucker, Trace Adkins, Josh Turner, Scotty McCreery, Granger Smith and many more. He started Sea Gayle Music which made tremendous waves on Nashville’s Music Row as an indie publisher. In 2016, Frank started Fluid Music a joint venture with Spirit Music Group, and in 2019 he was named CEO of Spirit Music Nashville. As a writer and producer, he has had 42 #1 singles, 75+ Top 20 songs and multiple certified multi-platinum/platinum/gold records. Rogers has co-written a slew of #1 songs: “I’m Gonna Miss Her” (Brad Paisley); “Alright” and “This” (Darius Rucker); “Five More Minutes”, “This Is It”, “In Between” (Scotty McCreery); and “Backroad Song” (Granger Smith).

Licensing with Spirit: License Frank’s music HERE.